From Slums to Luxury, Meet the Architects Behind Sydney’s The Old Clare Hotel

How a fenced-up brewery and an old school corner pub were ‘unbuilt’ as the centrepiece of a Chippendale’s hospitality precinct.

Walking down an immaculate paved laneway with quaint terrace facades and street-level restaurants bursting with vitality, it’s hard to imagine Kensington Street, Chippendale had ever been anything other than a mecca of hospitality. It couldn’t be further from the truth. For most of its 250+ year history, the area was one of Sydney’s most lurid neighbourhoods.

In spite of its central location and the thriving CBD next door, Chippendale carried run-down buildings, a reputation for drugs and prostitution and generally, a wayward past. The area’s houses were described by the City Health Officer in the 1850s as, “in the most wretched condition.” The reputation seemed unshakable.

A perfect foundation for a world-class boutique hotel and hospitality precinct? Why not!

This was the vision that led a team of developers from Fraser Properties, architects from TZG and hoteliers from the Unlisted Collection to create what has since become one of Australia’s most celebrated luxury hotel destinations.

So how do you establish a boutique hotel and dining precinct from a brewery’s administration block and a run-down corner pub? Tim Greer, Director at TZG Architects explains.

“I guess they were dishevelled but with good bones. You know, they were well dressed people who’d had a wild night out,” he says of the buildings prior to commencing the Old Clare Hotel and Kensington Street Main redevelopment back in 2012.

The Old Clare Hotel brings together the 19th century Victorian style Carlton & United Brewery Administration Office (formerly Tooths Brewery), the interwar period County Clare Hotel and a strip of 1840s terrace houses into one fluid design conceived as a collection of buildings, linked together and woven into the city.

The primary approach to the development lay in the art of unbuilding, where the emphasis was on what elements of the original buildings would be kept and accentuated. Tim explains that in unbuilding, rather than making removal a passive and negative process, it becomes positive and contributory.

“As architects you spend a lot of energy asking the question of, ‘well why would we build it like that?’ The corollary to that is to say ‘why would we unbuild it like that?’ and I find that kind of interesting. And in some ways it’s the nub of adaptive reuse as an architectural type is all about.”

This might be as detailed as deciding if or how to best remove an individual brick, says Tim.

“You can chip a brick out, or you can cut a hole in the wall. They’re two different expressions. Two very different architectural expressions.”

Multiply this level of detail across merging two buildings of different eras into one seamlessly joined experience and you can quickly get a sense of the consideration that goes into an adaptive re-use project of this scale.

“What I find very fascinating about this, as a kind of an architectural strategy is this idea that contemporary and historic architecture can exist at the same time. In doing so you get a very different view of history. It’s not about purity of a moment, but it’s about kind of a continuum if you like, it’s almost a cultural continuum that we as Sydney-siders have done different things at different times,” Tim says.

“There was some very interesting layers and some really uninteresting layers – you know, the kind of 1980s layers – you could imagine it with high hair and big shoulder pads, you know, in architectural terms, and so we kind of removed that. We did a couple of things, we removed some of the layers, but we also cut right through the building.”

The cohesive result places an arrival foyer at the precinct’s heart.

“The new foyer is in fact an old laneway that had been built over. Now when you go to the site it’s so clear that that was a laneway, you can see it. It’s part of the streets of the city.”

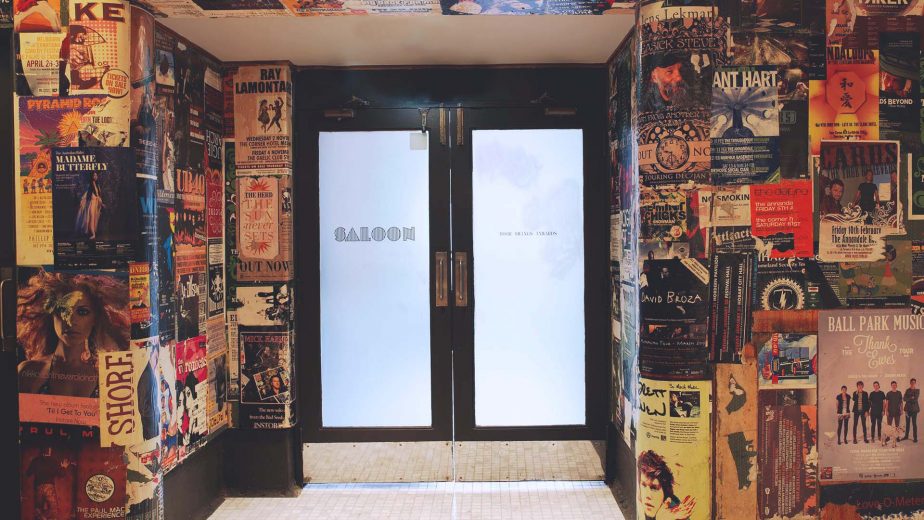

The foyer is just one restoration. Another notable accent is the ‘artistic’ carpet in the bar – the old carpet was sent to have its beer stains replicated. There’s also a wallpaper of digitalised music gig posters from the venue’s former life. Taking it even further, the whole floor structure of the original reception room was cut and lowered to street level to accommodate a series of restaurants.

“One of the other interesting examples is the Heritage Boardroom [one of the hotel suites]. It’s called that because one of the rooms inside the administration was the Boardroom for the Carlton United Brewery, so all the big decisions to do with beer were made in that room and therefore that had a material effect on Sydney and Australian society.”

“The bathroom for that boardroom was a gent’s only. When we think about that now it seems like a kind of strange thing, but back then in the 1920s or 30s it would have been normal because everyone that went to that meeting would have been a man.”

In the name of preserving such a unique glimpse into Sydney’s past, the urinal remains as the entry to the modern ensuite of the that suite; it’s marble and ornate these days.

The Old Clare Hotel is located in Chippendale, Sydney.